General Secretary To Lam to attend inaugural Gaza Peace Council meeting in US

19:05 | 23/03/2025 14:58 | 17/02/2026News and Events

On the occasion of the 14th National Party Congress, a major milestone opening a new phase of national development, Minister of Science and Technology Nguyen Manh Hung shared his perspectives on the role of science, technology, innovation and digital transformation as central drivers of Vietnam’s rapid and sustainable growth.

Minister of Science and Technology Nguyen Manh Hung.

Looking back at the 2021 - 2025 term, which changes do you believe have truly taken root and laid the groundwork for enhancing the economy’s competitiveness?

Nguyen Manh Hung: I believe the most outstanding result of science, technology and innovation during this period has not been any single achievement, but a profound shift in awareness, thinking and approach. We have laid the foundation for a new development framework in which science, technology, innovation and digital transformation are oriented toward outcomes, with socio-economic effectiveness as the central criterion. The entire chain from research and application to commercialization has been placed within a development problem-solving logic, rather than operating in a fragmented manner.

These substantive changes are most clearly reflected in three aspects.

First is the establishment of an enabling institutional framework, focused on removing bottlenecks so that science and technology can move quickly into everyday life, production and business activities. In the final year of the term alone (2025), the volume of legislative work was substantial and left a clear mark. The Ministry of Science and Technology took the lead, in coordination with relevant agencies, in drafting, amending and submitting 10 laws and one resolution for passage by the National Assembly. At the government and prime ministerial levels, 23 decrees, one resolution and five decisions drafted under the Ministry’s leadership were signed into force. This policy system reflects a strong determination to “unlock” institutional bottlenecks, long regarded as one of the greatest barriers to the development of science, technology and innovation.

Second is the significant improvement in digital infrastructure and digital governance capacity, which has gained international recognition. According to United Nations (UN) assessments, Vietnam rose 15 places in the 2024 E-Government Development Index, ranking 71st out of 193 countries. In telecommunications, Vietnam’s internet speeds have climbed sharply, placing the country among the regional leaders and within the global top 10 - 15 according to international evaluations. Fourth-generation (4G) coverage exceeds 99.8%, fifth-generation (5G) reaches more than 91% of the population, 100% of communes and wards are connected by fiber-optic broadband, household fiber penetration stands at 87.6, and smartphone usage is estimated at over 85%. These figures indicate that Vietnam has moved from “digitization” to “data-driven operations,” with digital infrastructure becoming a foundation for more effective governance and reduced costs for citizens and businesses.

Third is the strengthening of innovation capacity and the startup ecosystem, contributing to an improved national competitive position. Vietnam ranks 44th globally on the Global Innovation Index and is recognized as one of nine middle-income countries with the fastest improvement in rankings over the past decade.

In my view, the most valuable outcome of the 2021 - 2025 period is not merely the statistics, but the momentum that has been established: innovation embedded in business operations, digital transformation integrated into the functioning of the economy, and results-based governance gradually becoming the norm.

Scientific and technological achievements are often not immediately visible in daily life. From your perspective, over the past five years, in what concrete ways have citizens and businesses benefited most clearly from administrative procedures and public services to production capacity and product quality?

Nguyen Manh Hung: I would point to three groups of the most tangible changes. First is the transformation in how the State serves citizens and businesses. Administrative procedures and public services have become more convenient and transparent thanks to digital transformation. Paperwork has been reduced, travel minimized, and waiting times shortened. By 2025, nearly 78% of applications for fully online public services were processed end-to-end online, while almost 84 percent of public services recorded online applications. These figures demonstrate a strong shift from “queuing and waiting” to a digital environment for administrative handling.

Second, the capacity and productivity of enterprises have improved markedly and in greater depth through the application of technology and process innovation. Automation, digital governance and data utilization enable businesses to optimize operations, shorten production cycles, reduce errors, save materials and energy, and enhance supply chain management efficiency.

From the citizens’ perspective, as digital transformation becomes comprehensive, the digital space is emerging as a new living environment, where essential services in education, healthcare, finance and commerce are delivered rapidly and in a personalized manner, ensuring that everyone can participate in and benefit from the digital ecosystem.

Citizens benefit through convenience, businesses through productivity and quality, and the State through enhanced governance capacity. That, in essence, is the most substantive measure of science, technology and innovation in everyday life.

Cleanroom at the Nano and Energy Center, University of Science, Vietnam National University, Hanoi, a hub for semiconductor education and research. Photo: Giang Huy

You have emphasized that the key distinction of Resolution 57 lies in results-based management. Could you specify the goals and indicators that demonstrate this approach?

Nguyen Manh Hung: Previously, science management was guided by an administrative mindset: strict control of inputs, down to individual documents and invoices, while requirements and evaluation of outputs were insufficiently clear or robust. As a result, creative space was constrained, and scientists spent more time on procedures than on research. Resolution 57 reorders priorities by shifting from process-based management to management based on objectives and final outcomes. It also emphasizes pilot mechanisms and the acceptance of controlled risk. Without accepting risk, innovation is impossible.

This shift is quantified through clear, measurable targets. First is the indicator for growth quality, with the contribution of total factor productivity (TFP) to economic growth targeted at over 55%. This is a crucial signal that Vietnam’s future growth must rely primarily on productivity, science, technology and governance innovation, rather than continued expansion of capital and labor.

Second is the goal of developing at least five digital technology enterprises on par with those in advanced economies. This reflects the understanding that science, technology and innovation cannot be spread thinly, but must focus on creating powerful “locomotives” capable of leading ecosystems and generating spillover effects across the economy.

Third is measuring research outcomes by their ability to enter the market. Resolution 57 sets a target for the commercialization rate of research results and inventions at 8 - 10%. This marks a clear shift from viewing acceptance as the endpoint to recognizing it merely as a technical milestone, with real value lying in application and commercialization. The output of science is not the number of report pages, but the number of “Make in Vietnam” technologies and products that are deployed, sold in the market, and solve national challenges.

Fourth is the allocation of at least 3% of annual state budget expenditure to science, technology, innovation and digital transformation, with gradual increases in line with development needs. At the same time, management is shifting from detailed expenditure control to outcome-based lump-sum funding; from reclaiming research results for the State to granting ownership rights to research organizations for commercialization; and from fixed remuneration for researchers to benefit-sharing mechanisms when commercialization succeeds.

Science can only truly thrive when it is nurtured by the market. Accordingly, Resolution 57 sets the target for research and development (R&D) expenditure at 2% of GDP, with more than 60 percent coming from society. The State plays the role of “seed capital.” When businesses invest their own funds in science, they demand real results. That market pressure is the most natural and effective oversight mechanism for realizing results-based management.

In 2025, the Ministry of Science and Technology took the lead in drafting, amending and submitting 10 laws on science, technology and innovation to the National Assembly, widely seen as a major step in removing institutional bottlenecks. Could you elaborate on how these bottlenecks have been “unlocked” for research, innovation and technology commercialization activities, particularly for enterprises?

Nguyen Manh Hung: When we speak of “institutional bottlenecks,” we are essentially referring to long-standing barriers: excessive procedures, management approaches overly focused on process control, limited space for experimentation, insufficient incentives related to ownership and exploitation of research outcomes, and a technology market that has yet to function as a true flow.

Therefore, the National Assembly’s passage of 10 laws in the fields of science, technology and innovation is not simply about adding more legal documents, but about creating an entirely new framework that opens up fresh development space for science, technology and innovation. In several areas, Vietnam has taken a pioneering role globally, such as with the Artificial Intelligence Law and the Digital Transformation Law.

The clearest breakthrough in this round of institutional reform lies in a fundamental shift in the mindset governing science and technology management. For the first time, many provisions are designed to acknowledge the inherent nature of scientific and technological activities, which involve risk, failure and experimentation, while emphasizing that risks must be managed rather than eliminated through excessive procedures.

Enterprises are now clearly established as the center of the innovation ecosystem. They are no longer merely recipients of technology, but are enabled to participate from the very beginning: leading research tasks, placing research orders, collaborating with universities and research institutes, and, most importantly, benefiting from clearer mechanisms regarding ownership rights, exploitation rights and commercialization rights for research outcomes , including those formed using state budget funds, under transparent principles. When enterprises have rights and tangible benefits, they are more willing to invest in R&D and to persist with innovation.

Technology commercialization has also been freed from technical bottlenecks. Procedures for technology transfer, valuation of intellectual property assets, capital contribution using patents, technical know-how and research results have been streamlined to become more efficient and transparent. This shortens the path from the laboratory to the market, turning knowledge into products, services and added value.

Another important breakthrough is the opening of legal corridors for new technologies and new business models through controlled sandbox mechanisms. Many innovations cannot be licensed under existing laws, yet cannot be left unregulated. Sandboxes create a policy space that allows enterprises to conduct lawful, limited and supervised experimentation, before scaling up, thereby fostering innovation among businesses and startups.

Finally, research is being more closely linked to market demand and development needs through mechanisms such as commissioning, public - private partnerships, and linkages between the State, academia and enterprises. When research problems originate from real-world needs and have a clearly identified “buyer,” research moves more quickly into application, and social resources are mobilized more effectively.

Over the past five years, Vietnam has made significant gains in the Global Innovation Index (GII) rankings. Beyond state budget funding, what measures has the Ministry implemented to unlock private capital, venture capital and international resources, thereby realizing the goal of making Vietnam a dynamic regional startup hub, as you proposed at the ASEAN Digital Ministers’ Conference?

Nguyen Manh Hung: Innovation can only be sustainable when capital flows are effectively unlocked. In this context, the role of the State is to create enabling mechanisms and provide initial momentum.

First, we have focused on completing the legal framework so that private capital, venture capital and international funding can flow into the innovation startup ecosystem in a transparent and controlled manner. The Law on Science, Technology and Innovation provides the legal basis for the establishment of national and local venture capital funds using state budget resources.

We regard ecosystem connectivity as a decisive factor. The Ministry of Science and Technology has intensified cooperation with major startup hubs in the region and globally, such as Singapore, South Korea, Japan and the US, while organizing and elevating initiatives like Techfest and various investment and innovation forums. These efforts help build confidence among international investors that Vietnam is a serious market, with stable policies, a robust pipeline of projects and strong capital absorption capacity.

In addition, clearly identifying priority sectors is one of the most effective ways for the State to guide capital flows. On this basis, Vietnam has identified 11 groups of strategic technologies, focusing on areas that ensure national autonomy and resilience, have strong market demand, sufficiently large markets and the potential to generate long-term competitive advantages. These include foundational and cutting-edge technologies such as artificial intelligence, semiconductors, digital technologies and green technologies, as well as technologies supporting energy transition, healthcare, agriculture, defense and security.

When the State defines major challenges and sets long-term priorities, investors can clearly see the destination and the roadmap, making them more willing to commit long-term capital rather than pursue short-term gains. Capital flows most strongly when guided by a clear strategic vision and policy consistency.

I continue to believe that for Vietnam to become a dynamic regional startup hub, it does not need to compete through short-term incentives, but through the quality of its ecosystem: transparent institutions, a sufficiently large market, high-quality human resources, and strong regional and global connectivity. When these conditions converge, capital will naturally flow in.

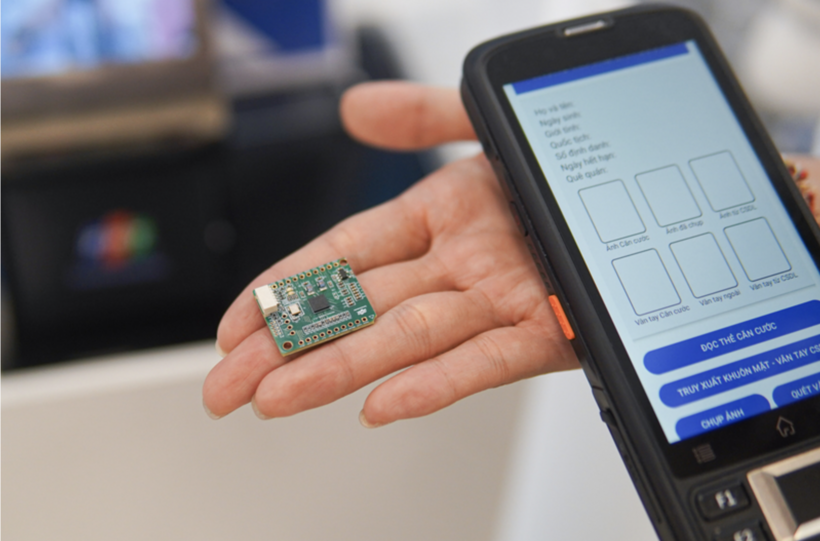

Semiconductor chip on display at the VIIE 2025 Innovation Exhibition, October 2025. Photo: Luu Quy

The draft documents of the 14th Party Congress emphasize a new growth model, the goal of double-digit growth, and the requirement for sustainable development. In your view, what strategic solutions are needed to translate science, technology and innovation into productivity, growth quality and concrete competitiveness in order to realize these objectives?

Nguyen Manh Hung: The new growth model emphasized by the 14th Party Congress places science, technology and innovation at the center of socio-economic development, transforming them from sector-specific activities into cross-cutting drivers of national progress. To achieve double-digit growth that is also sustainable, science, technology and innovation must convert macro-level objectives into productivity, growth quality and competitiveness through a set of strategic solutions.

First is institutional completion. Institutions must move ahead to open the way for innovation. A legal framework must be established for identified priority sectors, alongside the implementation of controlled sandbox mechanisms. Lawmaking approaches must also change: science and technology evolve rapidly, and legislation cannot wait five to ten years for revision. Where necessary, laws should be adjusted annually, focusing each year on one or two critical issues.

Second is mastering strategic technologies and emerging industries. Vietnam must remain steadfast on the path of self-reliance and self-strengthening, maintaining control over core technologies. Priority resources should be concentrated on semiconductors, artificial intelligence, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), advanced materials and new energy, while gradually developing space and quantum industries. These will serve as new growth poles, determining the country’s position and competitiveness in the next stage of development.

Third is a fundamental reform of the management model for national science and technology programs and financial mechanisms, with results as the primary benchmark. This entails a decisive shift from “spending on research” to “commissioning and purchasing research outcomes,” and from input-based management to output-oriented investment. At the same time, intellectual property and standards must be regarded as tools for guiding development.

Fourth is the development of modern science, technology and digital infrastructure. The focus should be on national shared data platforms, data centers, high-performance computing and AI centers, key laboratories, and a modern, synchronized postal and telecommunications infrastructure.

Finally, it is essential to develop a science, technology and innovation ecosystem grounded in talent. Without talent, there can be no strong science; without strong science, there can be no strong nation. Mechanisms must be robust enough to attract and retain top talent; to effectively implement the “triple-helix” model, in which enterprises are the center, universities and research institutes form the core, and the State plays a facilitating role; and to unlock capital flows for innovation, particularly through public - private venture capital funds.

19:05 | 23/03/2025 14:58 | 17/02/2026News and Events

19:05 | 23/03/2025 14:56 | 17/02/2026Trade

19:05 | 23/03/2025 14:55 | 17/02/2026News and Events

19:05 | 23/03/2025 00:12 | 17/02/2026News and Events

19:05 | 23/03/2025 08:30 | 15/02/2026News and Events